Sylvia

David Antrobus Posted on

David Antrobus Posted on  Friday, May 15, 2015 at 5:22PM

Friday, May 15, 2015 at 5:22PM  We always said if we were still haunting this earth a decade on, we'd meet at our spot like a Linklater couple, at the place where we learned—like movie fan neophytes—that love can encompass place and lighting and mood every bit as much as touch and taste. We weren't to know then that changes wrought by our kind's cold-eyed rapacity would render that decade the longest, slowest death rattle ever, our world's understated expiration.

We always said if we were still haunting this earth a decade on, we'd meet at our spot like a Linklater couple, at the place where we learned—like movie fan neophytes—that love can encompass place and lighting and mood every bit as much as touch and taste. We weren't to know then that changes wrought by our kind's cold-eyed rapacity would render that decade the longest, slowest death rattle ever, our world's understated expiration.

Yet I am here amid the wreckage, and I wonder whether you are too. Or did you get waylaid, along with the billions of others, somewhere between the comfort of sleep and the dawning unease of emerging wakefulness? Will you appear out of the brown air, through the oily miasma of a new atmosphere, as I sit waiting for you, patient as an ancient cedar counting the centuries before the arrival of the first antlike bipeds with saws? I have nothing else to wait for, other than the obvious oblivion awaiting us all, awaiting everything. This awfulness that's happened has stripped the flesh from the bones of truth, revealing a white unlovely thing: we are here to simply bide time before we die.

Will you make it? I am here now, in the warm ambient remnants of dark wood and soft lighting, this womb-cave once rumoured to be where silent movie stars came to die. Can you hear the low susurrus of conversation and the clink of glasses while "Enjoy the Silence" bleeds prettily from hidden speakers and we get gently drunk on extravagant caesars? We must use our imaginations like weapons turned inward. Nostalgia is the spirit's suicide. Can we—ought we to?—still imagine the waiters and bartenders and diners huddled at tables, and see beyond the broken leaded glass to a street where once we watched people park cars in the tightest spaces—now rusted cockroach frames on crumbling pavement—where we smiled at the joy of dogs, and where hope glittered on the wave tops in the bay instead of unpalatable toxic things?

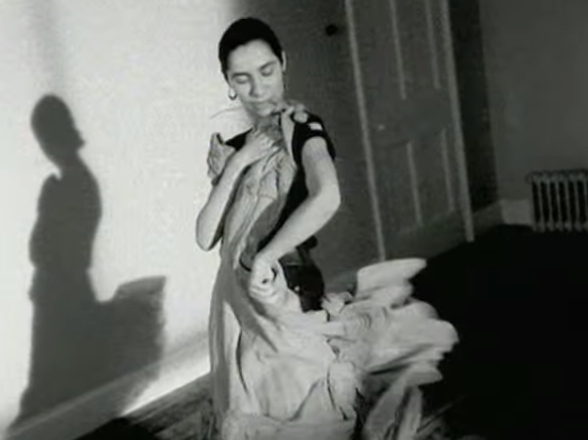

We once believed the fabric of our lives were woven from threads so fine that no one could unpick them, yet unraveled is how we've become in the merciless onslaught of reality. The lonely face looks out to sea. We were once on the sands, the surf growling like a feral pack. Now I'm alone in a shell of a building, gazing at petroleum waters.

You're not coming, I know; there will be no sequel. No redemptive beauty will emerge from the beige air. Your blacks, tying you to a past run aground and the barren oilspill of blighted hope, truly crackle and drag. The world is turning the mirrors backward, opening the nozzles on the cold stove, and covering the gaps in the doors with towels.