I was thinking about how writing dovetails with our wider lives, the lives we may lead outside the tiny cramped space in which we sit for hours hunched over a screen that slowly eats the cones and rods from within our dark-shadowed eyes, perhaps even the sanity from behind our knitted brows, lost amid a precarious landscape built from stacked pizza boxes and empty wine bottles and other far less wholesome things. You know… that place outside we call “the world”? I ventured into my corner of it recently (Vancouver, British Columbia) and even there I began to notice the marks and stamps left by other writers. Either that or I’m now so delusionally obsessed with writing I’ve reached the point of developing a serious pathology.

Vancouver’s most acclaimed literary figure was probably Malcolm Lowry, who wrote Under the Volcano here. William Gibson and Douglas Coupland also spring to mind. But I don’t really mean that. I’m not so much interested in the indisputably famous and lauded, but more the quieter language moments we sometimes stumble on by accident.

A case in point is the Fairmont Pacific Rim Hotel in downtown Vancouver. If you are ever in town, it’s an otherwise fairly nondescript piece of modern architecture (think steel, concrete and green-tinted glass) at the intersection of Burrard and Cordova, but what makes it remarkable is that a one-line poem wraps around 17 stories of its facade. Written by British artist Liam Gillick, it reads:

A case in point is the Fairmont Pacific Rim Hotel in downtown Vancouver. If you are ever in town, it’s an otherwise fairly nondescript piece of modern architecture (think steel, concrete and green-tinted glass) at the intersection of Burrard and Cordova, but what makes it remarkable is that a one-line poem wraps around 17 stories of its facade. Written by British artist Liam Gillick, it reads:

“lying on top of a building the clouds looked no nearer than when I was lying on the street”

Understated and minimalist, its impact undoubtedly dependent upon its being experienced in context, it nevertheless offers a patina of beauty to an otherwise ordinary late winter day in the city; a reminder that language, as abstract as we sometimes suppose, can also be such a visual and visceral thing of the world.

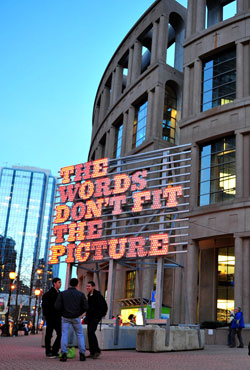

And that isn’t all. I found myself at the main central library and once again, even before entering what is frankly a stunning building in its own right, more understated words introduced themselves to me like slightly reticent predators.

And that isn’t all. I found myself at the main central library and once again, even before entering what is frankly a stunning building in its own right, more understated words introduced themselves to me like slightly reticent predators.

THE WORDS DON’T FIT THE PICTURE

Which is artist Ron Terada’s poetic expression of Vancouver’s historic relationship with bright, neon signs. Or as he puts it himself: “The sign takes its cues from an era of signage when signs were seen as celebratory, grand and iconic – in effect, as landmarks in their own right, a kind of symbolic architecture… Taken within the context of a public library, the work touches upon – in a very poetic way – the use of words and language as boundless and imaginative, as a catalyst for a multiplicity of meanings.”

And still we weren’t done, because inside the breathtaking atrium, there were yet more words, way up on the precipitous walls. Mysterious and, again, quietly poetic words. This time, it required some detective work to discover their source, detective work that hasn’t paid off at the time of writing (if my inquiries pay off, I’ll add any new information later). Here are those words, in the form of six banners hung beside each other (no idea how to format that here), all upper case text, each six-line block in different but uniform colours:

WITH

MEMORY

OF ALL IT

WOULD

LEAVE

UNDONE

FIRST

THROUGH

FOLLY

AND THEN

NOW BY

ERROR

LIKE A

HOPE

AGAINST

HOPE AND

WHATEVER

ELSE

IT WAS

NOW

THERE

AGAIN TO

BE MADE

REAL

HAVING

BEEN

WRITTEN

AT SOME

PRIOR

POINT

IN THE

FACE OF

ALL IT

COULD

HAVE

BECOME

Enigmatic and elusive words, somehow sorrowful, regretful. Certainly beautiful. Which could lead to a whole other blog post on how important language is as something beyond mere communication and more like art, but I’ll resist as this is getting long.

Enigmatic and elusive words, somehow sorrowful, regretful. Certainly beautiful. Which could lead to a whole other blog post on how important language is as something beyond mere communication and more like art, but I’ll resist as this is getting long.

Funnier still, this strange journey through some kind of secret poetic life of my adopted city didn’t end there. Retiring to one of my old favourite haunts, a little bar in Gastown, the oldest part of Vancouver, named the Irish Heather, all four bathroom doors were festooned with…. you guessed it…. words. Words written by Samuel Beckett, Shane MacGowan, Sinéad O’Connor and Brendan Behan, the latter of which seemed to encapsulate the day.

"I have a total irreverence

for anything connected

with society,

except that which makes

the roads safer,

the beer stronger,

the food cheaper and

the old men and old women

warmer in the winter and

happier in the summer."

Anyone else know of similar examples in their own cities, where solitary words must compete quietly against the rush of traffic, the roar of floatplanes in the harbour, the blustery cacophony of pigeon wings … and sometimes even triumph?

* * * * *

A version of this post appeared on Indies Unlimited on March 2, 2012. David Antrobus also writes for Indies Unlimited and BlergPop. Be sure to check out his work there if you like what you read here.